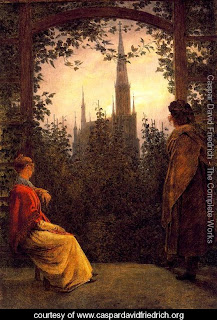

How is Christ's mission accomplished in a complex and ever changing society in which it's hard for many to take the very idea of church seriously? Following my last post I've been idling through more of the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and I came across 'Watching the church'. This isn't a picture I know anything about but again like Friendrich's many other works it's worth pondering. I think it's evening. The falling sun of the lengthening day makes the outline of the gothic church stark. The gothic form is clear and detailed despite the sharp light. Indeed the light suggests promise and hope radiating from that gothic shape.The two viewers are intent on the church with no hint of present conversation between them. They are themselves framed by an arch in the garden, perhaps part of a larger wooden structure, but its shape is much simpler than the complex building towards which they are staring. Have they come from evening worship and are pausing to look back and consider what has been? Or, is it that they haven't got as far as the church and its worship? The density of the foliage just in front of them suggests the latter. Today, at least, they haven't got as far as the church.

How is Christ's mission accomplished in a complex and ever changing society in which it's hard for many to take the very idea of church seriously? Following my last post I've been idling through more of the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and I came across 'Watching the church'. This isn't a picture I know anything about but again like Friendrich's many other works it's worth pondering. I think it's evening. The falling sun of the lengthening day makes the outline of the gothic church stark. The gothic form is clear and detailed despite the sharp light. Indeed the light suggests promise and hope radiating from that gothic shape.The two viewers are intent on the church with no hint of present conversation between them. They are themselves framed by an arch in the garden, perhaps part of a larger wooden structure, but its shape is much simpler than the complex building towards which they are staring. Have they come from evening worship and are pausing to look back and consider what has been? Or, is it that they haven't got as far as the church and its worship? The density of the foliage just in front of them suggests the latter. Today, at least, they haven't got as far as the church.

The artist is clearly 'at home' with the structure of gothic architecture - and yet there is a hesitation or reserve expressed in the watchers. They are obvously attracted by its beauty; but only from a distance. Like so many they 'look on' and wonder. Maybe they are longing to be part of this distant beauty, but maybe they are not. Will they join the artist at being 'at home' in this structure? We don't know. The artist poses the question whether his vision can be theirs?

It's so easy to assume that others long to share a living faith when in fact all they wish to do is to 'look on.' Like the artist those of faith have to be thoroughly 'at home' in ancient forms so that those forms remain clearly living traditions, but that doesn't necessarily turn onlookers into participants.