|

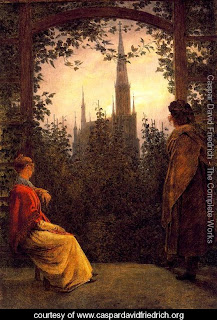

| Ecce Ancilla Domini 1850 |

That might be the retelling of those ‘penny drop’ moments of

my own past: standing in the gloom of an ancient abbey as part of the bass line

of a school choir and suddenly realizing with dub-struck awe the significance

of the words of O Come, O Come Emmanuel;

seeing the light of something beyond words in the sparkling eyes of an Alzheimer’s

sufferer’s rare smile at the pulling of a Christmas cracker; recognizing in the

playful determination of a small dog in deep snow a thread of life-joy that

mysteriously connects sensate beings; or finding a gaggle of excited young

children suddenly still and quiet as the story simply told touches them. Fortunately I could tell of many such

instances, but their power, though real, is so hard to recreate as a third

party retelling. Where then should I

look for inspiration?

As is so often the case, looking back might be a key. Looking back at what the stream of tradition

we inhabit might offer. And that brings

me to a painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti – Ecce Ancilla Domini (The

Annunciation), painted 1849-50. What Rossetti

portrays is the frailty of a young woman, a slip of a girl; a simple shift

clinging to her figure, her arms bare, suddenly awoken from sleep perhaps, her

knees drawn up, she cowers against the wall of her sleeping room. She is thin, troubled looking, and possibly

feeling threatened. She avoids looking

directly at the presence that has invaded her room. She certainly doesn't look as if she

considers herself favoured - much perplexity sums it up. As one scholar suggests, Mary's exclamation

at the end of the encounter, "Let it be to me according to your word"

is more a shrug of resignation faced with the inevitable within the world of

the sexual politics of first century Palestine, than the triumphant consent we

usually take it to be. The painting is

suggestive of that fearful acquiescence.

Rossetti's version of the story of the angel Gabriel

announcing to Mary her pregnancy and its purpose has none of the studious

contemplation and noble acceptance of traditional renderings so beloved of

Renaissance artists. This is a radical

reinterpretation in which the humanity - the bodiliness if you like - of Mary

is plain to see. Her holiness is

apparent by the halo, but the posture and the look make her clearly a woman not

a superhuman saint. The women figures of

the pre-Raphaelite painters like Rossetti do have a romantic, otherworldliness

about them - but those ethereal faces and forms all the more emphasise the

feminine, passionate, mysterious and sensual nature of flesh, human flesh.

The picture is almost wholly restricted to white and the

three primary colours - a curious goldness hangs around the angel’s feet, blue

drapes signify heaven and the virgin, red hair brings to mind Christ's blood,

and the whiteness of cloths and the lily mark purity. The symbols that any earlier artist might

have used are all there - yet the picture makes a new statement. When it was exhibited in 1850 criticism

rained down on Rossetti and he vowed never to show it again in public.

The Church sees fit to label this cowering girl the Blessed Virgin

Mary – we should hear that not such much as a title but as a description of her

body. Virgin here can designate nothing

else but a body. Her swollen womb is

just that, her carrying as tiring as any mother-to-be's carrying, her labour as

painful and exhausting, her birthing as bloody and as emotional as any

birthing. God will be born a body of a

body. And we will carol the promise of long

ago made new again in amniotic fluid spilt, a slimy form squealing and

stretching in air for the first time, and breasts heavy with milk.

That's wonder; that's gospel. God is born a body to make holy every body. A place to begin .....

The sermon woven from this strand is here.